Back to archives | Back to FOFA Gallery

CONCERNING SISYPHUS

Annie Lafleur

Walking the wild mountain in a storm I saw the great trees throw their arms.

Anne Carson, Gnosticism VI.

The printmaker’s memory is an ever-changing place; here the chemistry of ideas is registered. The printmaker works in reverse to reconstruct the work, and must continually scrutinize it in the interval between the final concept and the finished work. The surfaces become an endless reflection of the initial idea on which the artist assembles the inks and passes the paper through the press. These repetitive gestures, enlisted in one and the same effort, are perceived in the aesthetic decisions as so many cycles to maintain. Hands encountering matter continuously shaping the image through the workings of the press: it is the labour of Sisyphus, rolling a massive rock up a hill only to let it go a few feet from the top. Between the numbing action of the gestures and the utter lucidity of a vital movement, the boulder produces meaning that denies finiteness, turning to the rejuvenation of ideas. It is the artist’s imagination that expands the boundaries. When the rock slips from the hands of Sisyphus, creativity is set in motion, far from toil, filtering in behind the scenes of existence. Sisyphus is human in wanting to regain control of his fate, and also in evading the absurdity of the gestures in order to free himself from the physical constraints. The human condition is expressed at the heart of this struggle, between the rapture and the drama of the work.

Sisyphus is the hero of Greek mythology who defied Death and confronted the gods with a love for Life. For this, he was condemned to roll a rock up to the top of a mountain, but refusing to reach its zenith, he lets the stone fall back down. Here, the artist presents the issue from every angle. What happens to the human being who is intensely involved in creating a work while life goes on outside without them? What happens to the neglected work when life becomes animated without effort or transcendency? Creating is the motivation that distances the artist from death, like Sisyphus letting the block succumb to gravitation. The artist and Sisyphus celebrate life by having an acute awareness of death, a subject both shaped and shunned.

Here, in this harsh scene, the master printer intervenes as the work’s interpreter and keeps it balanced towards an ideal state. The artist and collaborator engage in a dialog that extends the work towards a poetics of creation. In this paper then, there is a double consciousness from which the work draws its substance. The artist’s intention and the printer’s skilful hand come together to evoke the richness of discourse, and then converge with the other. And this third party lets Sisyphus down and he looks deeply into the forsaken sphere of his reflection. The transfer of actions becomes blocked on the course marked out for him by the gods. But where the hero reigns, man is truly impassioned and freed from the fate of hurtling down the hill, here the feeling of a new beginning is still possible. In the same spirit, the printmaker keeps a balance in the creative space between the distance imposed by the stages of production and the contiguity of involvement with the material. All activity right away drives him closer to his goal. From now on, our hero is the artist and the interpreter of his life although his creative power is asymptotic. Sisyphus is the immutable idea of creation.

The works displayed here evoke reflections of the self as well as doubt and the violence of the demiurge. Barbara Steinman’s work, Traces in Red (2003), directly embodies this relationship to the myth of Sisyphus, paraphrasing the last line of Camus’ text: “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” The edge of the book, creating a slope and stained like blood, shows all the humanity of Sisyphus’ repetitive gesture and refers at the same time to that of the printer. It illustrates the mountain’s one worn side, produced with 86 diminishing sheets to suggest the refusal to climb to the top of the mountain, which would be 100 sheets in all. This work culminates in the tragic meaning of Sisyphus and the artist’s fate, putting the central activity of existential and artistic concerns back into context.

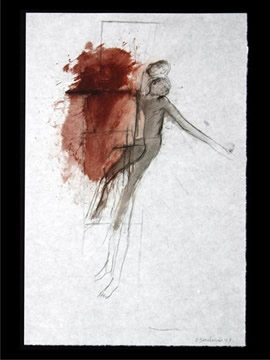

Sisyphus is happy, because he is the guardian of exclusive knowledge, divided in two: on one side, the collapse of meaning and the world, and on the other, the ascent of the self and of nonsense. By climbing only one side, Sisyphus already is failing. Betty Goodwin’s work is closely akin to this dichotomy with the bloody drama of the unfolding body (A Burst of Bloody Air, 2003) and with the body plunging into the unknown, where the bone, close up, becomes an allegory for death (Escape, 2003). It seems that the gods’ punishment suits some of Sisyphus’ desire: he becomes immortal. Refusing death, he is driven into the desert. In this desert land, the artist improvises in solitude: questioning, trapping, engraving and then slamming the door. The printmaker risks everything on the plate or stone, risks losing the produced work by having it swallowed up in the acid, by exposing it too long in the light or by scratching it too deeply. And the work is still insufficient. The very principle of an edition underlies the wish for the similar, the pitfall between a unique gesture and its duplication.

For Anne Carson, among others, the delicacy of the inks and the transparency of the paper give lightness to the cumbersome printing process, which goes to show that the workshop remains porous. The Gnosticism evoked by the title seeks this absolute knowledge in Sisyphus. The gnosis is in him like an ultimate revelation that engulfs the rock, disappearing “into the darkness” (R. Racine). The poems collected in this art book are filled with creatures caught up in darkness, revived by the reddened lure of citadels, where the self is absorbed. The self like “butter” slips into an initiatory phase between consciousness and exhaustion. Sisyphus reclaims his spirit on the side of the mountain when he attempts to recover humaneness in this immemorial night.

|

The rock represents a mass of similar knowledge, declining and complying with the creative act. Sisyphus has burned his hands on the infernal stone, which once abandoned makes him the gift of a painful body in a sterile world. Artists, for their part, look for meaning in the work while outside life is seething; they invite the fervour into their studio. Camus writes: “That hour [when the stone rolls back down without Sisyphus is] like a breathing-space … the hour of consciousness. … [when] he is superior to his fate.” The latter kindles creation while the artist becomes impassioned about the work, both of them conscious of the immutability of forms.

In this turmoil, Rober Racine’s vulture swallows its bare flesh under an enormous wing. It attempts to split the heads of men with its moist beak. This raptor with a ghostly red skull sits upright on charred trunks, indifferent to easy prey that inescapably hovers as morbid relief. The vulture is this rock that hardens in the sun and takes over the landscape, insistent death in the lair of the gods. Camus goes on: “There is no sun without shadow, and it is essential to know the night.” A monumental night in tenacious grass, here flowers discreetly transform the world and everyday disasters into grainy beauty (Geneviève Cadieux, Métis, 2004). In this anonymous-looking night one keeps an eye open, secret discovery in a solitary gaze: and a flower under the eyelids because one must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Translation by Janet Logan

Albert CAMUS, The Myth of Sisyphus, trans. Justin O’Brien, London, Penguin Books, 1975, p. 109.

Ibid, p. 110.

Stinger Editions

Stinger Editions, founded by co-directors Judy Garfin and Cheryl Kolak Dudek, publishes art prints and makes up a degree course in the Print Media program at Concordia University. Master printers are invited to teach printmaking and collaborate in the production of original prints. Several master printers such as Chris Armijo, Matthew Letzelter and Mikael Petraccia have participated in the program, teaching graduate and undergraduate students as well as mentoring students implicated in the collaboration between artist and printer. This exhibition is the first public presentation of the Stinger Editions archives.

Stinger Editions has published the original prints of Governor General Award winners Betty Goodwin, Barbara Steinman and Roland Poulin as well as MacArthur Foundation grant recipient Anne Carson. Other artists’ projects are print works by Geneviève Cadieux, Janet Werner, David Elliott, Ed Pien, Rober Racine and Pierre Dorion. And, François Morelli’s series of monotypes shows one the centre’s most recent projects. More than twenty or so images have been published, the corpus being represented by the following galleries: Galerie René Blouin, Galerie Joyce Yahouda and Galerie Pierre-François Ouellette in Montreal, Peter Kuhn Gallery in Calgary, Olga Korper Gallery and Robert Birch Gallery in Toronto and Tracey Lawrence Gallery in Vancouver.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Publication of the exhibition brochure was made possible through the generous financial support of Diane and Salvatore Guerrera and family. We would like to thank the following for their assistance in bringing this exhibition together: Galerie René Blouin, Galerie Joyce Yahouda, Galerie Pierre-François Ouellette, and the Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery, Concordia University in Montreal; the Paul Kuhn Gallery, Calgary; Olga Korper and Robert Birch galleries, Toronto; Tracey Lawrence Gallery, Vancouver.

We would like to thank Dean Christopher Jackson for his vision and initiative in supporting the Master Printer Program and Dean Catherine Wild for her continued support. To Rene Blouin we extend our deep gratitude for his enthusiasm and publishing collaboration. He is a true connoisseur of the arts and we greatly appreciate his expertise and counsel.

|

|