Back to archives | Back to FOFA Gallery

Cellular Memorabilia

video stills, Tissue Culture Point of View (2008) october 17 - november 11, 2011 “There is a longer duration that has to be accounted for when you are working with living systems, especially given the fact that you can cryo-preserve them for an extended period of time. There is the potential, for example, that the materials will outlive you. This happens with painting and other materials too, but with biological materials, you realize that there are dif- ferent thresholds of time and duration. You realize that there are other scales of time that are iperceptible to the human eye or our human sense of time. “ From Bio-Arts and the feminist politics of hands-on knowledge: An interview with Tagny Duff by Kim Sawchuk. n. paradoxa Vol 28. 2011 Pp 68-80. http://www.ktpress.co.uk/nparadoxa-volume-details.asp?volumeid=28

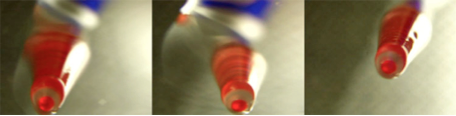

Cellular memory is a speculative idea and folkloric notion that personal and ancestral history and memories can be stored in ones own body at the cellular level. It also, not coincidently, refers to a memory card used to store information in cell phones. The desire to merge human biology with computational/electronic enabled devices and extend human lifespan and memory can be found in popular culture, science fiction and in laboratory science. Today, through the practice of tissue culture and bioengineering, cells are grown and regenerat- ed in the laboratory. Synthetic viral vectors are used to both track and manipulate genetic infor- mation in cell cultures and fleshier specimens, such as skin samples. Custom designed viruses are constructed with computational algorithms via database sequencing and tissue culture engineering wet lab technologies, thereby jumping across the biological and digital divide; the division between synthetic and natural life and categories defining the human and non-human. The lifespan of these cellular entities may also exceed that of the donor’s. The notion of cellular memorabilia, in this context, is reconfigured through an engagement with the process and tools of biotechnology to explore a complex array of desires and fears embed- ded in the search for increased lifespan and memory. Departing from the utopic vision of immor- talized lifespan and unlimited memory capacity, the exhibition explores the idea of memory as unstable and constrained by the limitations of biotechnology and the fallibility of visualization tools. This exhibition features three works that utilize the tools and practices of tissue culture engi- neering to reflect upon the changing status and perception of bodies at the turn of the post- biological era. The Living Viral Tattoos (2008) is a series of four tissue samples of human breast tissue donated by an anonymous donor from elective breast reduction surgery. The samples are transfected with a biological virus, Lentivirus, and fixed with immunohistochemical stains to produce the appearance of bruises. Tissue Culture Point of View (2008) features a video instal- lation that reverses the anthropocentric gaze of the microscope placing the gallery visitor in the role of the cellular tissue specimen. Cryobook Archives (2010) is a portable library of frozen human-animal viral tissue bound into the form of books. The work reflects on the history of early surgical practices in Europe that sought to extend and preserve the lifespan of human tissue through the practice of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the binding of books made from human cadavers. The following is an excerpt from an interview conducted by Dr. Kim Sawchuk with Tagny Duff. It is published in its entirety as Bio-Arts and the feminist politics of hands-on knowledge: An interview with Tagny Duff by Kim Sawchuk. n. paradoxa Vol 28. BIOPOLITICS, 2011 Pp 68-80.

Tagny Duff: Living Viral Tattoos was the first work that I did with human tissue, and using Len- tivirus, a synthetic derivative of HIV Strain 1. Upon reflection, I see it as a sculptural prototype informing the development of the Cryobook Archives. The same protocol that was used and developed for the Living Viral Tattoos was used for the Cryobook Archives although it changed a bit.

Kim Sawchuk: Why an interest in the tattoos? Tagny Duff: Well, my first impression of going into a science lab was that the pipetting tool is completely ubiquitous. You need to use a pipette for almost everything in the wet lab. Like a needle, it is a tool for marking bodies. Every time that I pipette liquid or cells into a petri dish or cells, I am impacting that substrate. Even if you can’t see the design with the naked eye, the pipette allows me to manipulate and mark the structure of that material. So it became a way of thinking about tattooing.

Kim Sawchuk: What did you learn about the changing status of the human body as a result of doing experi- ments and learning these protocols? Tagny Duff: Tissue culture engineering is a very disciplined and regulated mode of engaging with biomaterial. The lab is a sterile environment. It’s a very controlled setting: it’s its own world. It is not necessarily a reflection on the world, although it is supposed to be. The idea of working in vitro, as being synonymous with the world outside of the lab, is perhaps a fallacy. From working in the lab, I realize that there is an interconnection across various scales of organic cellular life forms but they are not necessarily always compatible. There are entities like viruses and bacte- ria cohabitating with humans or animals, but they have a singularity and impersonal force in a petri dish that may not be the same as when humans are walking around in the city. I was thinking that here is a piece of skin that has a virus being transplanted into it. It also has different types of contaminants in it. The skin lives for a certain amount of time in the petri dish before its cells are no longer viable or alive. The skin in the petri dish dies, but the human host still lives for the time being. It could also be true in the reverse– the cells from the skin could be cultured and then survive well beyond the life of its human host. Tissue culture engineering introduces a shift in the human relationship the materiality of the human body. For me it is about an understanding of an expanded relationship with non-human forms that make the human.

Kim Sawchuk:. If “viral tattooing” was a sculptural prototype, then what happened in your next project, the Cryobook Archive? The Cryobook Archive project has so many layers to it because it also harkens back to technologies and practices of book-making and book-binding. It returns us to the idea of the critical impor- tance of temporality in your artistic research, by establishing a resonance between the posthuman present and the past. It indicates that those practices and pasts aren’t so far in the past as we tend to think. Tagny Duff: Exactly. I feel it is necessary to acknowledge the importance of craft in biotechnology, bio-medical science, and science itself. Tissue culture engineering and biomedi- cal surgery can also be seen in relation to other types of craft technologies, like book binding. At one point, bookbinding was a high-tech practice, and has now become a craft that has lost its status as a mode of information reproduction. Perhaps I wanted it to knock our understanding of bio-technology down a couple of notches. [laughs] I wanted to be a little more playful with it, and challenge the idea of functionality within bio-technology and science.

Kim Sawchuk: I want to follow up on this. What are some of the feminist dimensions that are embedded in your practice of bioart that may not be so overt? Does it live in the moments where you experience, tangi- bly, this relation between art, craft, and science in your process? Tagny Duff: Definitely. While working in the SymbioticA lab I was introduced to the work of Kira O’Reilly. Her project “Marsysus- Running out of Skin” consisted of making lace out of tissue cul- ture. I was really excited about Kira’s work and how she blended craft and mythology with tissue engineering practice. While doing more research, I was also introduced to Anna Dumitriu’s work with bacteria which she used to make different types of ornate designs on women’s clothing (see n.paradoxa vol 20, 2007 pp.5-12). She started a group ,Conceptual Craft, where artists are really pushing the envelope of craft in the context of bio-tech and experimental media practices. I think that there is an interest in making that connection to craft, which has been traditionally associated with women’s work, but is very much a part of this type of scientific practice, especially in lab-based work.... Dr. Honor Fell was one of the major tissue culture engineers from Cambridge University’s Strange Way Labs. She did a lot of thinking about what it means to be in the lab working with tis- sue and in her writing attempted to demystify this new emerging scientific practice. Highlighting the history of craft implicit in the practice of biotechnology and particularly tissue culture engi- neering, helps to demystify the high-tech glamorous, slick images of biotech that people usually encounter. When I work with tissue culture engineering tools and protocols from the perspective of a craft it opens up a space to think about the practice and materiality I am engaging with in a direct and tangible way. [...]

Kim Sawchuk: Could you talk more about the layered complexity of the Cryobook Archives as a sculptural object and its continuing existence as a living object? Tagny Duff: After I had finished the Living Viral Tattoos Project, I felt that I needed to push the material further. While researching and working on the project I stumbled upon the history of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the making of anatomical books with the skin from human cadavers. I became fascinated about this practice, its relationship to what I was doing in the lab, and to the changing nature of bio-technology. When I learned that surgeons had been using the skin of ca- davers that they had operated on to bind anatomical books, I realized that there is thisrelatively unknown history of using human tissue as a way of honoring the deceased body and the lives of patients. Imagine how amazing and horrifying surgery would have been as a new technology. When you are operating on bodies there’s a whole shift in perception in terms of how the human body is visualized. So the Cryo-books seemed like the right form for me to talk about these intersecting histories. It also allowed me to make sense of time, not only through history. In making this work, I knew I could keep it cryo-genetically preserved for some period of time, but was it for a long time? Who knows, right? And I’ve always been interested in that, in terms of documentation and preservation practices for archives. Where, why, and for how long, do we want to preserve and conserve an archive? ... I wanted to see how long I could sustain the Cryo-books, and turn it into an archiving project, and not just as a comment on preservation and archiving. This would also create more tangible tools and problems within the art practice itself. No longer am I just in the lab, working with the problems of the lab, like the wetware to make the work and thinking of all the amazing ideas that come out of that. This project means that the lab has moved into the art world. Cryo-books converges concerns about preserving and conserving memory and bodies, which is what both fields have in common.

+++++++++ Tagny Duff is an interdisciplinary media artist working across video, performance, bioart, net art and installation. Duff’s current work explores the murky terrain of life, liveliness and what is perceived as live in the post-biological era. By working hands-on with biotechnology and scientific techniques that are used in scientific laboratory practices to manipulate life, Duff generates uncanny images, objects and experiences that introduce viewers to visceral encounters. The works explore (and provoke) a reflection on the changing status and scale of bodies as they migrate across digital and biological platforms. Dr. Kim Sawchuk is the editor of the Canadian Journal of Communication (www.cjc-online. ca) and co-editor of wi: journal of mobile media (www.wi-not.ca). A feminist media studies scholar, her research and writing has long addressed the relationship between embodi- ment, discourses and experiences of technology. Her current work on this subject traverses two major areas: wireless, mobile communications and biomedical imaging. She has been a Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies, University of Bologna. She was also an invited lecturer at the University of Silesia, Poland and the University of Lancaster and the University of Manchester, England.

The artist acknowledges support for the following: Tissue culture engineering support and collaboration for Living Viral Tattoos: Dr. Stuart Hodgetts, Ionat Zurr, Maria Grade Godinho, Dr. Jill Muhling, Oron Catts at SymbioticA, The Centre for Excellence in Biological Arts at The Department of Anatomy and Human Biology, University of Western Australia, with lab support from Greg Cozens and logistics Jane Coakley. Cryobook Archives: Engineering consultation and collaboration of display unit, David St.Onge. feasibility design, Jean-Michel Dussault and Benoit Allen. Construction of cryobook display unit by Alain Gagné Inc., Xavier Seaborn, and Amélie Trépanier. Donation of glass by Multiver, (Quebec). Technical support by Antonia Hernandez and Maya Ersan for video installation and Genevieve Ruest for construction of sculptural units. Thanks; Miriam Posner, jake moore, Kim Sawchuk, Matt Soar, Vanessa Rigaux, Antonia Hernandez, Genevieve Ruest, Kendra Besanger, all the staff and techs at FOFA.

|

|---|

© Concordia University